The Maya calendar is a cultural artifact from the general

category of the World Ages. Computing the long-term cycles of

cosmic order was a concern in all ancient cultures from China to Peru. The

introduction of calendars to regulate civic life and agricultural planning

was a long and complex process. In devising these systems, the calendar-makers

did not limit themselves to time in the human scale, but extended their

computations to countless thousands of years. Doing so,

they sometimes came up with remarkable figures.

In Hindu chronology, the number 4,320,000,000 is associated with the cosmological motif of the "Days and Nights

of Brahma." This number caught the attention of Joseph Campbell,

who observed that 4,320,000,000 years, or 4.32 billion years, is intriguingly

close to the current estimate for the geological age of the earth, 4.5

billion years.

4320 is the base number that generates the four Yugas of Hindu cosmology.

It also shows up in the chronology of prediluvian kings compiled by the

Babylonian priest, Berossus, and elsewhere. It is an artificial norm

(a sacred canonical unit, if you prefer) that also factors into various

geological, sidereal, solar, lunar, and planetary time cycles.

Like the Hindu timescale, Maya calendrics runs into the range of remote, unimaginable numbers. The mathematician-priests

who devised the Maya calendar recorded exact dates of events, down to

the day, but they also liked to extrapolate far backward and forward

in time. The precision of their planetary, solar, and lunar tables is

impressive. They calculated the cycles of Venus and the Earth as accurately

as we do today, down to four decimal points. This mastery of verifiable

time-cycles commands respect, and obliges us to look closely at their

long-term extrapolations. For the Maya and all other ancient peoples,

verifiable and non-verifiable calculations were integral to a single

system of sacred calendrics. I see nothing woolly-minded in granting

some respect to their long-term timeframe, especially if something can

be

learned from doing so.

According to most experts, the Long Count dates from early

in the Classical Maya era, 200 - 900 CE, although it may be much older

in conception, possibly originating among the Olmecs in the 7th C. BCE.

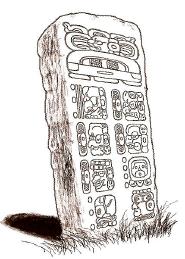

The engravings that record the earliest dates are Chiapas de Corzo, Stela

2, 32 BCE, and Tikal Stela 2, 292 CE. The last date recorded was January

909 CE. The calendar uses a string of five units factored on a 20-base: k´ín (1

day), winal (20 days), tun (360 days of 18 winals), katun (7200

days or 20 tuns) and baktun (144,000 days or 20 katuns).

According to most experts, the Long Count dates from early

in the Classical Maya era, 200 - 900 CE, although it may be much older

in conception, possibly originating among the Olmecs in the 7th C. BCE.

The engravings that record the earliest dates are Chiapas de Corzo, Stela

2, 32 BCE, and Tikal Stela 2, 292 CE. The last date recorded was January

909 CE. The calendar uses a string of five units factored on a 20-base: k´ín (1

day), winal (20 days), tun (360 days of 18 winals), katun (7200

days or 20 tuns) and baktun (144,000 days or 20 katuns). The stele or engraved stones with calendric glyphs record dates by hieroglyphs and dot and bar notations, showing the units by position. Scholars notate the dates in five placements, from baktun to k'in, like this: 9.16.0.2.0, equivalent to June 18, 751 AD. December 21, 2012 is written 13.0.0.0.0. There are three standards of correlation and, you bet, a lot of quibbles and fine tuning in Maya chronology.